This post was originally published on this site.

Laura KuenssbergSunday with Laura Kuenssberg

BBC

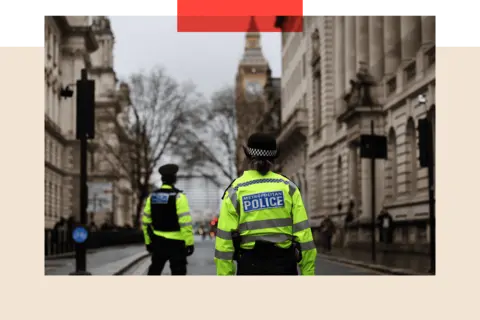

BBCThere is an “epidemic of everyday crime”, the home secretary says, such as shoplifting and phone theft.

It reminds Shabana Mahmood of the years when she worked on the till in her parents’ corner shop, with a cricket bat under the counter ready to deter shoplifters who stole, time and again.

While overall crime has been going down in recent years those types of offences have been going up, matched by rising public anxiety.

“Will I get my phone nicked? Will I get burgled? And if I do, will the police even answer my call?”

Those are questions a former Home Office minister describes as “the most basic” from voters who, not unreasonably, expect governments to keep them safe.

Faith in the police has been battered by scandals and mistakes too – whether that’s the horrific crimes of a small number of serving police officers, or the astonishing clangers committed by the West Midlands Force, and the chief’s initial refusal to quit.

Whichever way you look at it, there’s widespread political agreement the way the police is set up just doesn’t really work.

But there’s no such easy consensus on the solution.

What’s the plan?

Enter the home secretary with a plan she’s describing as the biggest set of changes since the police was founded two centuries ago. Politicians could rarely be accused of understatement. And Mahmood could rarely be accused of hanging around.

Her proposals will be revealed in full on Monday, but we already know she wants to dramatically reduce the number of police forces in England and Wales from 43 to a dozen or so, although she will not prescribe a number.

Sources have told the BBC police officers will have to have professional licences, like doctors or lawyers, that they’ll be expected to renew every few years. The government wants ministers to have the power to fire Chief Constables who they think aren’t up to scratch, and send crack teams into forces that are failing.

And “the biggest change of all”, another insider tells me, is the creation of one big national force, expected to be formed by merging the National Crime Agency (NCA) with Counter Terrorism – currently led by the Met – and other elements of national policing.

The Home Office won’t confirm the full details of what that organisation could look like. But it’s not the first time politicians have been tempted to think that bigger will be better.

In 2006 Labour introduced what was nicknamed “Britain’s FBI”, the Serious and Organised Crime Agency (SOCA). After it frankly didn’t live up to the expectation, the Coalition government replaced it with the NCA. It was again – would you believe it – dubbed “Britain’s FBI”.

But now, according to several sources, that too is likely to be put together with other organisations to become a huge behemoth responsible for tackling the lot.

Why? Well, one former home secretary suggests a simple logic. “Most forces just aren’t capable of dealing with serious and organised crime, whether it’s trafficking or financial crime.”

They’re often driven by international networks, they argue. So whether it’s merging forces at a local level or creating one national mega force, it’s about responding to how crime has changed, they argue.

“Police needs to be both bigger and smaller, these days it’s big international organisations that set up the criminality that afflicts small communities,” the former home secretary said.

They and other insiders admit the changes are also partly to address the blunt question of cash.

PA Media

PA MediaThe Home Office has a massive budget, but compared with other government departments has not had lavish settlements in recent years. Remember Yvette Cooper holding out for more in last ditch talks with Rachel Reeves last year?

“The elephant in the room is the money,” a senior figure says.

The Home Office reckons it’s right to get rid of some “ridiculous” anomalies that result from having 43 separate forces – forces buying trousers and helmets, or IT devices separately, rather than clubbing together to try to get a good, cheaper deal for taxpayers.

Another insider says the changes make sense because the “landscape is cluttered”, with too many different national-level initiatives trying to tackle different kinds of problems. Better to have one big organisation working with more streamlined local forces – well, perhaps.

Andy Rain/EPA – EFE/REX/Shutterstock

Andy Rain/EPA – EFE/REX/ShutterstockLabour tried, and failed very publicly, to make this happen last time they were in power. It was the idea of the police inspectorate, not the government, but the then Home Secretary Charles Clarke wanted to scrap more than 20 forces for reasons that sound very familiar today and ran slap bang into a wall of resistance.

There were objections from some forces, opposition politicians and in the end, the plans were ditched.

The Conservatives this time round will make the same argument, already questioning what evidence there is to show that cutting the number of forces makes any difference to cutting crime, or whether a force is any good or not.

They accuse the Met, the biggest force, of having the lowest rates of solving crimes, and it’s had scandal after scandal.

In Scotland too – where eight forces were merged into one by the SNP years ago – hundreds of millions of pounds have been saved, but it’s had a string of high-profile problems too. Don’t be surprised if there is a very noisy opposition argument about the risk of mega forces losing their links to local communities. And police chiefs becoming directly accountable to the home secretary and Parliament rather than the scrapped local police and crime commissioners could give rise to accusations of a power grab.

Policing is, by principle in this country, operationally independent from ministers. If forces are bigger, and judged and controlled more directly by the home secretary, does that principle get stretched?

PA Media

PA MediaSo will the plans actually come to pass? Even though the government has a mega majority, given the number of wobbles, and the longer and longer list of plans that have been ditched, it is a valid question to ask any time major changes pop up.

And scrapping a couple of dozen forces was “very, very bruising last time round” for Labour, one insider says.

There is a crucial difference this time.

Senior police officers, including Sir Mark Rowley, who argued for these changes on our programme months ago, are largely on board. The rank and file may take a very different view.

The Police Federation questions what a reorganisation will do for morale among overworked officers, and whether the proposed changes will make a difference, telling us: “The case for change is clear, but police leaders’ track record on big change is dismal. Fewer forces doesn’t guarantee more or better policing for communities.”

When it comes to licences, the federation is particularly aggrieved saying doctors and lawyers “have industrial rights that police officers don’t have and are also far higher paid”.

“Minsters have used the analogy of making police officers ‘match fit’. Policing is broken and officers are on their knees, not match fit,” it said.

“The service is the most inexperienced it’s been in living memory, resignations, assaults on officers and mental health sickness absence are all at record levels.”

The plans are also likely to take years to come into force. Mergers will start with that government classic, a consultation, in the hope that broad consensus can be found rather than a clash. Wise, perhaps.

But it means the possible changes are many years away, and have a long journey through Parliament where there could be big fights that could turn ugly. And there is a challenge for the home secretary to make the argument that shows these huge changes will make any real difference to people’s lives.

No-one ever daubed “POLICE REFORM NOW” on a placard.

Even one source who backs the plans is sceptical. “There’s zero political reward, and high political risk… Will the next home secretary think in a few years time, ‘Well, this is all a bit awkward?'”

But other observers reckon this is exactly the kind of big move a government with an enormous majority should make – an important structural change that might not win punter-friendly plaudits but will update and modernise an outdated public service.

Mahmood’s fans reckon she can’t – and won’t – waste any time. The home secretary might not have a cricket bat under the counter these days, but she seems up for a fight.

Top picture credit: PA/Getty

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. Emma Barnett and John Simpson bring their pick of the most thought-provoking deep reads and analysis, every Saturday. Sign up for the newsletter here

![[Aggregator] Downloaded image for imported item #655481](https://www.sme-insights.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/0b836a00-f871-11f0-a422-4ba8a094a8fa.jpg.webp)