This post was originally published on this site.

Priti GuptaTechnology Reporter

A reliable supply of computer chips is essential for Arnob Roy, the co-founder of Tejas Networks.

His company, based in Bangalore, India, supplies the equipment behind mobile phone networks and broadband connections.

“Essentially, we provide the electronics that carry traffic across telecom networks,” he says.

That requires special chips designed for telecoms tasks.

“Telecom chips are fundamentally different from consumer or smartphone chips. They handle massive volumes of data coming simultaneously from hundreds of thousands of users.

“These networks cannot go down. Reliability, redundancy and fail-safe operation are critical – the chip architecture has to support that,” Roy says.

Tejas designs many of those chips in India, a country well known for its expertise in designing computer chips (also known as semiconductors).

It’s estimated that 20% of the world’s semiconductor engineers are in India.

“Almost every major global chip company has its largest or second-largest design centre in India, working on cutting-edge products,” says Amitesh Kumar Sinha, Joint Secretary of India’s Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology.

What India lacks is companies that manufacture semiconductors.

So Indian firms like Tejas Neworks design the chips they need in India, but then have them manufactured overseas.

The weakness of that system was exposed during Covid, when the supply of chips dried up and companies in all sorts of industries had to scale back production.

“The pandemic made it clear that semiconductor manufacturing is too concentrated globally, and that concentration carries serious risk,” Roy says.

That spurred India to develop its own semiconductor industry.

“Covid showed us how fragile global supply chains can be. If one part of the world shuts down, electronics manufacturing everywhere is disrupted,” says Sinha.

“That’s why India is developing its own semiconductor ecosystem to reduce risk and increase resilience,” he adds.

He is leading government efforts to develop the semiconductor industry, which involves identifying parts of the production process where India can compete.

Getty Images

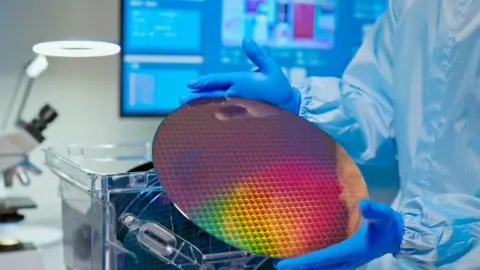

Getty ImagesThere are several steps in making a computer chip. First design, where India is already strong.

The second stage is wafer fabrication, where thin sheets of silicon have circuits etched on to them by extremely expensive machines in huge factories known as semiconductor “fabs”.

That part of the process, particularly for the most sophisticated chips, is dominated by companies in Taiwan, with China trying to catch up.

In the third stage those large silicon wafers are sliced up into individual chips, packaged in protective casing, connected to contacts and tested.

That third stage, known as Outsourced Semiconductor Assembly and Test (Osat), is the part of the production process targeted by India.

“Assembly, test and packaging are easier to start than fabs and that is where India is moving first,” says Ashok Chandak, president of India Electronics and Semiconductor Association (IESA).

He says that several such plants will “enter mass production” this year.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFounded in 2023, Kaynes Semicon is the first company to get a semiconductor plant up and running with support from the Indian government.

Kaynes Semicon invested $260m (£270m) in a factory to assemble and test computer chips in the northwestern state of Gujarat. Production started in November of last year.

“Packaging is not just putting a chip in a box. It’s a 10 to 12 step manufacturing process,” says Raghu Panicker, CEO of Kaynes Semicon.

“That’s why packaging and testing are as critical as making the chip itself without this stage, the wafer is useless to industry.”

His facility will not be making the most advanced computer chips found in the latest mobile phones or used for training AI.

“India does not need the most complex datacentre or AI chips on day one. That is not where our demand is, and that is not where our strength lies today,” Panicker says.

Instead, they will be the kind of chips used in cars, telecoms and the defence industry.

“These are not glamorous chips, but they are economically and strategically far more important for India. You build an industry by first serving your own market. Complexity can come later. Scale has to come first,” he adds.

It’s been a steep learning curve for Kaynes Semicon.

“We had never built a semiconductor cleanroom in India before. We had never installed this equipment before. We had never trained people for this before,” Panicker says.

“Semiconductors demand a level of discipline, documentation and process control that is very different from traditional manufacturing. That cultural shift is as important as the technical one.”

Getting staff trained has been a huge challenge.

“Training takes time. You cannot shortcut five years of experience into six months. That is the single biggest bottleneck,” Panicker says.

Back in Bangalore, at Tejas Networks, Arnob Roy is looking forward to buying more locally-sourced tech.

“Over the next decade, we expect a significant semiconductor manufacturing base to emerge in India and that will directly help companies like ours.”

It’s the start of a long journey, he says.

“I do see Indian companies eventually designing and manufacturing complete telecom chipsets but it will take patient capital and time.

“Deep-tech products take longer to mature, and India is only now beginning to support that kind of investment.”

![[Aggregator] Downloaded image for imported item #682992](https://www.sme-insights.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/cb9f63c0-f5e2-11f0-b385-5f48925de19a.jpg.webp)