This post was originally published on this site.

At the start of 2025, I said that investors should “beware the long bond”. The good news is that yields on the longest-dated bonds did not run wild during the year. The 30-year Treasury and the 30-year gilt are ending where they began. Yes, the 30-year bund has gone from 2.6% to 3.5%, while the 30-year Japanese Government Bond (JGB) is up from 2.3% to 3.4%. However, this is healthy: a world in which investors were willing to lend money for three decades at incredibly low rates (well under 1% at times in Japan) is very damaged, and higher long-term rates are a step towards normality.

At the same time, we are seeing early hints of an important shift. While longer-term rates are not coming down, the short end of the yield curve is. With the exception of the Bank of Japan, central banks mostly reduced rates in 2025, including cuts by the Bank of England and the US Federal Reserve in December. This is likely to accelerate in 2026 in the US: markets are underestimating how aggressively Donald Trump and whatever thrall he appoints as Fed chair will try to cut rates to juice the economy.

Time for governments to issue more short-term debt

(Image credit: Bloomberg)

Rate cuts alone do not solve today’s big problem for governments. Central banks directly set the rate at which they lend very short-term money to commercial banks. Expectations for this largely set the path of short-term bond yields, but longer-term yields are determined more independently by markets. So even if short-term rates come down, higher long-term yields will still push up the cost of interest on public debt.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don’t miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don’t miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Whenever a bond issued at miniscule rates a few years ago has to be refinanced, the new rate shoots up. Thus the amount of interest that government pay is steadily rising. They can try to cut spending to bring down debt, but we constantly see that this isn’t politically possible.

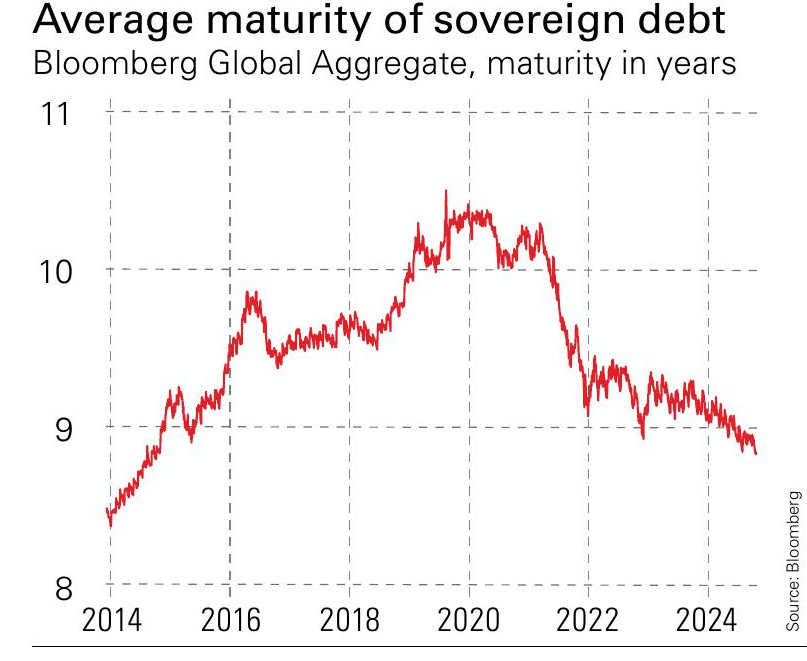

The obvious way out is to inflate away debt – but when markets expect higher inflation, they will demand higher yields to compensate, negating the gains from inflation. Central banks could hold down yields by buying up long-term bonds, but a decade of quantitative easing has shown us how much distortion this causes. The best option for now is to cut long-term debt issuance in favour of short-term debt, which pays lower yields. That is what we are seeing in countries including the US, the UK and Japan (that’s why average maturities of outstanding debt are dropping – see chart). However, a flood of short-term debt could unsettle markets and cause yields to rise. Note that earlier this month, the Fed launched a $40 billion programme of buying short-term bonds. It describes this as a technical move to manage market liquidity, but don’t be surprised if this is just the first step in central banks systematically buying short-term bonds.

So here’s a scenario. Governments issue more short-term debt. Central banks a) cut rates below inflation and b) buy more and more short-term bonds to keep yields down. Longer-term yields tick up, and the yield curve gets steeper. How will this affect markets? Is it inflationary? We should start to find out in 2026.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek’s magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

![[Aggregator] Downloaded image for imported item #420791](https://www.sme-insights.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/zrwPyrJsiCNmB4s9nR3Fu9-1280-80-1068x712.jpg)