This post was originally published on this site.

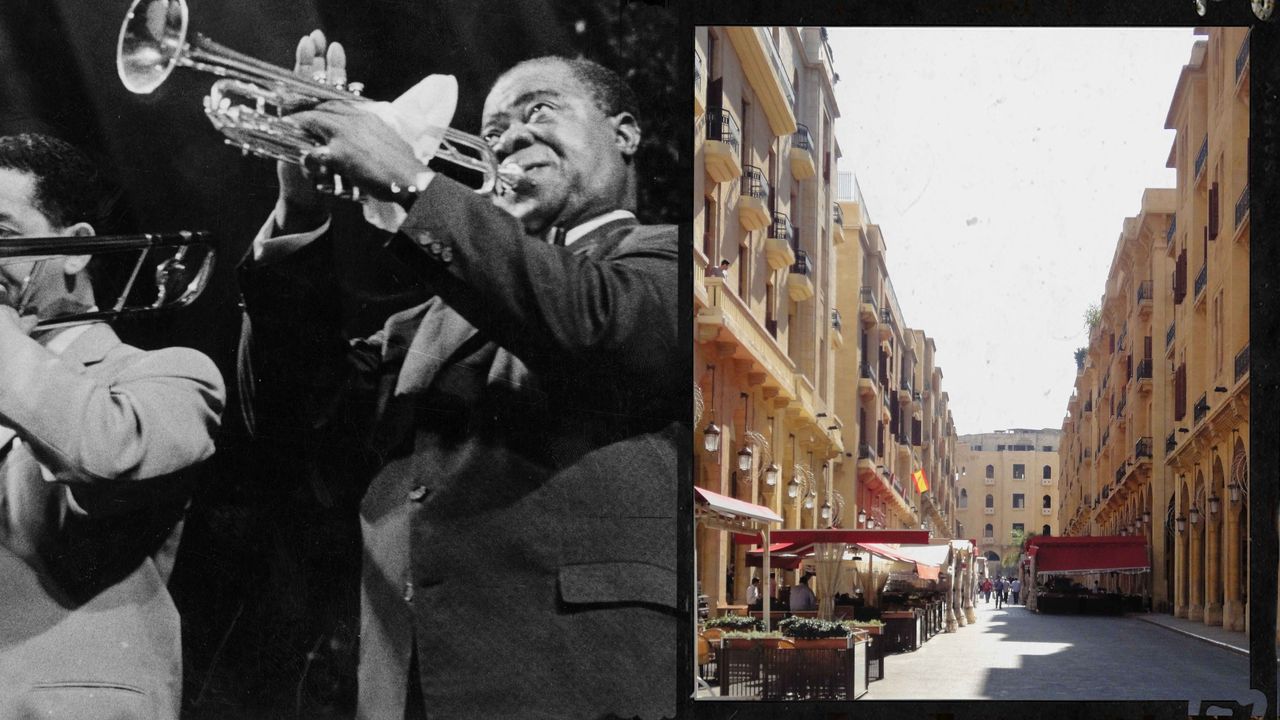

It is not just the flurry of new events and venues that is driving jazz forward in Lebanon, it is also a shift in the approach to the musical style. “After the Civil War, there was a rigidity in the scene, a sense that you had to mimic American standards to be good,” Hosn says. “Today, musicians are far more innovative, often incorporating local sounds and instruments.” One of the first to do this was the iconic Ziad Rahbani, a Lebanese musician who began mixing elements of jazz into his pieces in the early 1970s; his 1973 play Sahriyyeh (“An Evening Party”) is often cited as one of the first major works in which Western jazz harmonies were merged with Arabic melodies.

Today, musicians are drawing on Rahbani’s legacy. “Through experimentation with fusion styles I found I could alleviate the dissonance of the quarter tone in oriental music [as the maqam-based musical traditions of the Arab world and eastern Mediterranean is referred to] by using the jazz harmonic motion,” musician Lucas Sakr explains. “It makes the oriental music far more digestible for wider audiences.” Sakr also incorporates a range of traditional instruments, including the oud, buzuq, qanun, nay, and violin. In these pieces, maqam-based melodies (part of traditional Middle Eastern music) float above extended jazz chords and modern grooves, the rhythm section adjusting carefully when quarter tones appear. Sakr’s work has earned international recognition, even leading to a highly competitive scholarship to study jazz at HEMU Lausanne.

Sawma also experiments with various styles with his fusion trio band, Bonne Chose. “Our band blends jazz, psychedelic rock, dream pop, and synth wave,” he tells me. Sawma is also part of a ‘Fuzz Jazz’ trio that performs each Wednesday at Centerstage, a Beiruti house in Achrafieh that functions as an experimental music room and bar. “Each week we invite one additional musician—often from outside of the jazz world—to improvise with us,” Sawma says.

These initiatives have continued despite a series of recent upheavals, including the pandemic, ongoing economic turmoil and, most recently, Israel’s strikes accompanying a new period of regional conflict. “We have faced many challenges,” Naiim explains, “especially when it comes to finding grants to run Jazz Week. Most NGOs and grant providers have different priorities because of all the issues facing Lebanon.”

Last year, the society received no funding at all for Jazz Week, according to Naiim. The community still found a way to put on the events, however. “Some venues kindly provided free entry by securing external funds or using their own resources, while others offered reasonable prices for our guests.” In the end, the 2025 iteration of Beirut International Jazz Week managed to host a record-breaking 30 performances.

For Naiim and others, this persistence reflects a broader determination to ensure the longevity of Lebanon’s relationship with jazz. “Jazz is all about finding ways for wrong notes to sound good,” Hosn says. “The new styles in Lebanon honor that tradition, reminding us that from every dissonance, something beautiful can emerge.”

![[Aggregator] Downloaded image for imported item #688735](https://www.sme-insights.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Jazz20Beirut-1068x601.jpg)