This post was originally published on this site.

Tom Symonds

The Boston Globe/Getty Images

The Boston Globe/Getty ImagesWarning: This article contains themes you may find upsetting

Gina Russo was watching a gig with her husband-to-be, Fred Crisostomi, when she realised something wasn’t right.

Great White, an 80s hair-rock band, had opened their set with a thrash of guitar chords, as four large pyrotechnic flares shot out from the stage. The flares instantly set fire to the surrounding acoustic foam panels, installed to deaden the sound.

“It was immediate,” Gina tells BBC News. “It got bad very fast. The backflash just happened that quick.”

Then came “a black rain of smoke”, Gina adds, the heat melting, then shattering, glass lights above people’s heads. Gina and her fiance made for the nearest exit, a door to the right of the club’s small stage. A bouncer blocked their way, but Gina has no idea why.

That’s when “a stampede” began for the main exit, she says, and Fred desperately pushed her ahead in the crowd. Gina says “bodies were piling up” as people scrambled to get out – and her last memory was making it through the door to safety before passing out.

When she woke from an induced coma 11 weeks later, Gina learned her fiance had saved her life but had lost his in the fire.

This was 2003, at The Station nightclub in the snowy town of West Warwick, Rhode Island, on the east coast of the United States.

Some 22 years on, there was a near-identical event at Le Constellation bar in the equally snowy ski resort of Crans-Montana, Switzerland, in the early hours of New Year’s Day 2026. At The Station nightclub, 100 people died and at Le Constellation, 40, mainly young people, lost their lives. Many survivors of both fires have severe burn injuries.

The two disasters have striking similarities, and not only in their appalling impact on victims. Both were caused by indoor pyrotechnics, experts say. Victims appear to have had little time to find an escape route, and foam panels may have spread the Swiss fire in an identical way to The Station nightclub fire.

UK fire investigation consultant Richard Hagger was quick to compare the two tragedies. He is “99% certain” the Swiss fire was triggered by the sparklers. He says if the foam had been fire retardant it would have smouldered, not burned.

These similarities raise the questions: do we really understand how dangerous such situations are? And what should we do if we were to find ourselves caught up in one?

A matter of seconds to escape

In both the Rhode Island and Swiss tragedies, a “flashover fire” is thought to have taken hold. This is when hot air rises, but as the heat and smoke reach the ceiling there is nowhere for it to go. So it spreads downwards, quickly igniting furniture, clothes and skin.

In 2003, Phil Barr was 22, back home in Rhode Island for a winter break after living in New York. He was set on a career on Wall Street, but Phil loved a loud rock band, so going to see Great White that night sounded, well, great.

He got there early and when his friend arrived shortly before show time, Phil grabbed him a beer and excitedly propelled him to the front of the crowd.

As the fire began, the band’s lead singer turned and said, calmly over the PA system: “Wow, that’s not good.”

It wasn’t. Phil describes the moment of the “flashover”, saying flames quickly “got overhead, and it was above me”.

“All of a sudden, everything’s on fire, I could sort of see an orange glow, behind heavy black smoke but not much else,” he adds.

“It went from feeling the heat of flame to feeling like your entire body’s in an oven.”

In an attempt to escape, Phil ended up slamming his burning body at a side door and falling out into the snow, and safety. He suffered life-threatening respiratory damage.

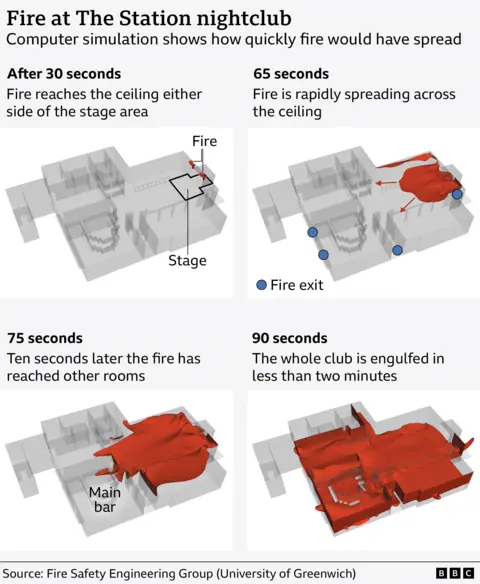

In an incredible coincidence, a camera crew from a local TV station was in the club, filming a video about venue safety. Their 12-minute footage of the fire shows it took just 25 seconds for flames to reach the ceiling, and within 90 seconds, toxic smoke had filled the building. With the doorway then blocked by people piling on top of each other and black smoke pouring from the windows, the video suggests leaving straight away gave them the best chance of survival.

Prof Ed Galea, one of the world’s leading experts on fire and the way people react to it, explains how heat coming from the flammable foam acoustic panels covering the ceiling in The Station nightclub fire made the situation much worse.

BBC/Ed Galea

BBC/Ed Galea“It’s a nightmare situation when the fuel is in the ceiling. You don’t have the advantage of the time it takes for the fire to develop. It’s already in the ceiling. You’ve got an instant hot layer and when flashover happens, survivability in any space is unlikely,” he says.

As part of the investigation into what happened at The Station nightclub, experts from the US National Institute of Standards and Technology built a laboratory version of the club and set it alight. Their official report found flashover conditions were reached after about 65 seconds. After 90 seconds “conditions in the middle of the room… were found to be lethal”.

Galea built on these findings, inputting the layout of The Station club into a computer simulator he created which predicts how fires spread. It showed a rapidly expanding burst of heated air, with temperatures inside the club reaching 700C within 80 seconds.

While the official investigation into the Swiss disaster is ongoing, footage gathered to date suggests this blaze also engulfed the room in a matter of seconds, spreading across the foam-lined ceiling.

Swiss authorities say the fire is believed to have been started by sparklers attached to champagne bottles raised too close to the ceiling during celebrations, and that the bar had not undergone safety checks for five years.

SUPPLIED

SUPPLIEDFire requires three things: heat, fuel and oxygen. And in a fire such as this, there is a window of seconds to make the decision to get out, before the flashover happens, Galea says. But every disaster Prof Galea has studied has convinced him that people underestimate the speed with which fires can spread.

‘Chance favours the prepared mind’

“We call it friendly fire syndrome,” he says. “We are not exposed to fire on an everyday basis any more, as we used to be 100 years ago when we were experienced at starting fires for cooking. We have lost all of that connection to how rapidly fire can develop.”

Hagger says “some people will stand and physically watch the fire, fixated by what they are seeing. They don’t physically perceive the danger. Some will film it, some will even try to hide, rather than escaping.”

In a famous study from 1968, psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley recruited male Columbia University students and asked them to fill in a form while smoke was pumped into the room. The researchers measured how many students stepped out to raise the alarm.

When they were in the room alone, 75% reacted to the smoke by raising the alarm. But when two other people were with them – who were in on the experiment and had been told not to react – just 10% of the subjects reported the possible fire.

The authors concluded that sometimes an “individual seeing the inaction of others, will judge the situation as less serious than he would be if he were alone”.

In The Station fire, crucial seconds passed before both Gina and Phil decided to get out, almost like they were waiting for something to happen.

“My initial reaction to the fire was, ‘Oh, that’s interesting’,” Phil says. “It almost looked like it was just sitting on the surface. It was going to burn out.”

“We’ve been conditioned to believe that there are fire sprinklers or extinguishers nearby, right? I remember thinking at one point, ‘We’re all going to get wet’. Obviously that didn’t happen.”

The Station nightclub did not have them.

The Boston Globe/Getty Images

The Boston Globe/Getty ImagesPhil’s account suggests others in the crowd may have reacted only when the sudden and devastating flashover happened. “You exit a fire in an orderly fashion. You don’t push,” Phil adds. But when people realised, “it just turned into chaos.”

Gina says it was the fire alarm triggering, which made people react – almost as if they had to be told to leave.

In the Swiss fire, footage showed some young party-goers filming the early stages of the fire or trying to put out the flames by waving jackets. On social media, some questioned their actions and were criticised for being insensitive. Galea says the way they acted was nothing to do with their age.

“People are saying, ‘It’s Gen Z, they don’t know what they are doing’, but it has been happening ever since I started doing research about this,” he says.

He has a mantra, which, he says, should guide anyone’s thinking when it comes to their safety in a fire: “Chance favours the prepared mind. You improve your chances by being prepared. Always look for the means of escape.”

Preventing another tragedy

According to Galea’s decades of research, there have been 38 similar fires claiming about 1,200 lives since the year 2000. Fifteen involved some form of pyrotechnics and about 13 involved acoustic foam or decorative materials.

Given these precedents, some may wonder why we do not appear to be learning the lessons.

While there are shared fire testing specifications, and an industry dedicated to improving safety, there is no internationally enforced “fire code”. The risk is that a fire in one country does not lead to action to prevent a very similar fire happening in another.

After the 2017 Grenfell Tower disaster in London, a public inquiry found the London Fire Brigade had been broadly aware of fires involving flammable cladding around the world, but had failed to properly prepare staff to deal with one.

Compare that with the international aviation industry, which has the advantage of being highly centralised. Air crashes are independently investigated, the findings shared globally, and international directives issued to fix problems, resulting in a good safety record.

Gina and Phil still live with the scars they received in The Station fire. Some 80 of the Swiss fire victims remain in hospitals in Switzerland and other countries.

Before that night in 2003, Phil was a competitive swimmer, but the smoke badly damaged his lungs.

“I had this fight to get my life back, he says. “I was not going to let these injuries hold me back or define me.

“I look at that moment and I say, ‘This is what I almost lost’,” Phil says. “I realised I need to go out and put the effort into the things which really matter.”

Gina still mourns Fred, whom she lost that night. She now has a new partner – her husband is a retired firefighter.

![[Aggregator] Downloaded image for imported item #587154](https://www.sme-insights.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/a95b2f20-f16d-11f0-a422-4ba8a094a8fa.jpg.webp)