This post was originally published on this site.

Alex ForsythPolitical correspondent

BBC

BBCA few weeks ago, I was driving along the M6 late at night, towards the West Midlands, when I came across the orange flashing lights and miles of cones that signify road works.

Two lanes were closed and the overhead gantry warned of a 50mph speed limit on the near-empty motorway.

My immediate reaction was an inward sigh. I clock up thousands of miles on Britain’s roads as a result of my job presenting a Radio 4 programme from a different part of the country every week, so I understand road works often mean delays – and that can lead to frustration.

Brett Baines has been driving a HGV for close to 30 years and says that he has noticed more road works.

“[They] seem to drag on for months, years,” he says.

Now, we’re likely to see even more works in England, according to National Highways, which manages the nation’s motorways and major routes, as our ageing roads undergo much-needed upgrades and repairs.

Much of the network was built in the 1960s and 1970s, as car ownership expanded – but those roads and bridges are now reaching the end of their “serviceable life”, explains Nicola Bell, the agency’s executive director.

In Wales, too, a large amount of highways infrastructure was built in the 1960s and 1970s. Drivers can expect some “essential maintenance work”, according to the Welsh government, though it’s less clear there, as well as in Scotland and Northern Ireland, whether disruption from road works will increase in the same way as it’s predicted to in England.

Problems on the roads have consequences. Most of us use roads to travel, but for many people they also mark a daily interaction with the machinery of the state, and they shape opinion of how well the country is – or isn’t – working.

Plus, there is a cost to the economy. In all, 2.2 million street and road works were carried out between 2022 and 2023 in England, according to the Department for Transport (DfT), costing the economy around £4bn through travel disruption.

It’s a fine balance between the benefits of improved infrastructure, versus the cost of disruption. But does the country have that balance right?

The scourge of street works

In the village of Clanfield in Hampshire, one resident, David, tells me he is frustrated. Utility companies have dug up the roads to replace old infrastructure, resulting in a patchwork of road closures and temporary traffic lights.

“We’re just coming up to the famous four-way set,” he says, approaching some temporary traffic lights. What frustrates him is how long they’ve been there.

“It’s had a huge impact,” he says. “The issue I have around here is the co-ordination of it all.”

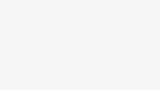

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSGN, which manages the gas network in the south of England, says it has been replacing 10 miles of ageing pipework. It is a “particularly challenging” project bringing “vital improvements”, they say. It is due for completion in May.

A spokesperson said: “[These] are for the long-term benefit of the local community and we are working hard to complete them as quickly and as safely as possible. We have maintained regular communication with the community throughout.”

Similar works are going on in other towns and villages.

Local roads have seen an increase in road works and street works – often to upgrade utilities like water, energy, and broadband. The Local Government Association of England and Wales (a body that represents councils, which are also highway authorities) cites a 30% increase in utility company works over the past decade.

For many residents, like David, that doesn’t make it any less frustrating.

“It’s necessary, I get that,” he says. But in his view it comes down to two things: “Communication and co-ordination.”

Money, fines – and the question of who decides

In England, councils are responsible for all highways other than major roads and motorways. When it comes to road works, some are carried out by councils (including patching-up roads in poor condition), while others are carried out by the utility companies.

Nick Adams-King, leader of the Conservative-run county council in Hampshire, admits the roads in his area are in poor condition; he says bringing them up to scratch would cost £600m.

“[But] our annual budget is around £70m,” he says.

The government has increased funding for highways maintenance. It says the budget for local road repairs will be more than £2bn a year by 2030, up from £1.6bn in 2026-27.

But there is another issue, says Adams-King. “The challenge for us is that the utility companies have a lot of leeway in their ability to influence when work is carried out.

“They also have the ability to declare some work an emergency piece of work, and as a consequence of that they can… put their diversion, their road closure, their temporary traffic lights in place, and only inform us six working hours later, by which point it’s often too late for us to be able to properly manage what’s happening.”

Local authorities employ various measures to reduce disruption, such as permit schemes, allowing them more control over how and when works take place.

However, councils have raised issues with one permit type – the “immediate permit”, used for urgent or emergency works, and where there is no requirement to warn local authorities in advance.

These accounted for almost a third of all street works in England in 2023-4. Some councils have suggested they are being misused.

One authority reported that a “crackly phone line” had been used as a reason for an immediate permit – even though it had been known about for weeks.

In pictures via Getty Images

In pictures via Getty ImagesIn July last year, a report by the House of Commons Transport Select Committee said these permits were essential but urged the government to consult on the definition of urgent works.

The government has also doubled the fines that local authorities can issue for street works offences (from £120 to £240).

Yet Streetworks UK, a body representing utility companies, insists most work – 69% – is carried out in a planned and co-ordinated way.

Clive Bairsto, its chief executive, says he doesn’t think utility companies are over-using immediate permits, adding: “The Department for Transport said there was absolutely no evidence to support that. I actually don’t believe there is abuse of the system going on.”

Cost to businesses around the country

At a small shopping precinct in Rochdale, Greater Manchester is a pet shop called Amber Pets. Inside it’s stocked with specialist pet food and animal toys and every kind of dog lead imaginable.

Its owner, Angela Collinge, has run it for 27 years – but now her business is being affected by road works. “As soon as one lot’s finished, another lot starts,” she says. “[There’s] just hideous congestion every morning.

“People avoid coming this way and then they don’t come into the shopping centre. We have seen a lot of regular customers disappearing.”

Utility companies in Rochdale say that essential works have taken place in the area to upgrade or maintain vital infrastructure, including gas pipes, water mains and broadband.

They said they co-ordinated with the local council, that works were done as quickly and safely as possible, and steps were taken keep local residents informed.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTwo firms are also trialling a new approach in which they carry out gas and water works simultaneously, to minimise disruption in the area. If successful, it could be extended.

But Paul Waugh, the local MP, believes they should be doing more. “They need to realise the damaging economic impact,” he argues.

He blames a long-term reliance upon “make do and mend”. He says: “We need a much better, more co-ordinated system.”

However, Clive Bairsto argues that the utilities companies do work hard to co-ordinate where they can.

The case of Wisley Gardens

This story of challenges facing businesses is told across the country.

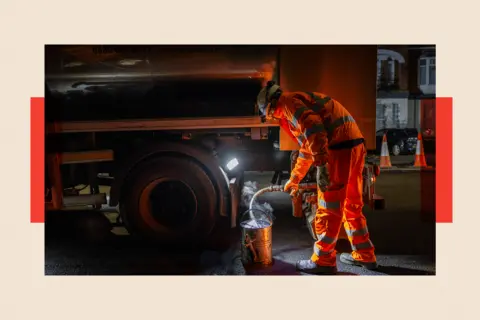

Clare Matterson, director general of the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS), points to their gardens at Wisley, near junction 10 of the M25 in Surrey.

Over the past three-and-a-half years, National Highways has spent over £300m on a project to improve congestion and safety at this busy junction.

But Matterson argues that her charity has lost nearly £14m as a result.

Getty Images

Getty Images“We’ve dropped over 350,000 visitors in a year,” she says. “We had families sitting in their cars, we have a lot of older visitors getting very stressed about driving in those very difficult conditions.

“People got in touch with us and have said, ‘We’ll either cancel our membership until this is all over or we won’t be coming visiting for a few years.’

“We’ve never disagreed that improvements should be made,” she adds. “But should it take so long? Should it have such a big disruption?”

And the project has been delayed, with an extra nine months of work that National Highways says is caused by extreme weather.

Now RHS Wisley is seeking compensation.

National Highways says it is attempting to minimise disruption by closing the M25 entirely over a series of weekends – an unprecedented step to speed up the works.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images“Actually, you [are] going to get more done by closing it for five weekends throughout the duration of the works than prolonging that disruption by perhaps just closing one lane,” says Nicola Bell of National Highways.

She adds: “We do have every sympathy with a business like RHS Wisley, when you are building something as complex as that upgrade right next to their business.”

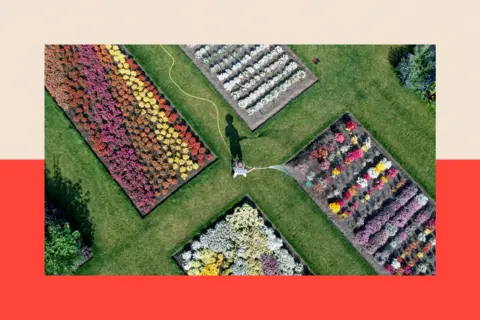

Motorway delays and ‘short sharp shocks’

Overall, motorways and major trunk roads (known as the strategic road network) account for just 2% of England’s roads by mileage, but it carries a third of all traffic and two-thirds of all freight.

Delays on England’s major roads increased between 2019 and 2025, in part due to road works.

According to a report by the DfT on the performance of National Highways: “The government is concerned with the rise in average delay and recognises how costly delays can be to businesses and how frustrating they are for road users.

“Addressing delays on the SRN (strategic road network) is a priority in driving economic growth.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe government has announced plans to spend £25bn on the strategic road network between 2026 and 2031.

Another new approach has been tested out in Hampshire, where a new garden village of 6,000 homes has been built that requires an extra junction on the M27 between Portsmouth and Southampton.

A concrete tunnel designed to run beneath the motorway was constructed in a nearby field, then slid into place. It meant closing a stretching of the motorway in both directions over Christmas while the work was carried out.

John Beresford, managing director of Buckland Development, which is building the village, said the idea was to minimise the disruption on the motorway.

“[We knew it was] going to be hell for all the local people for a bit of time,” he says. “[But it’s] a short, sharp sort of shock, hopefully minimising the long-term disruption.”

James Barwise, policy lead at the Road Haulage Association, says short-term whole-road closures can have merits – though he acknowledges they can be “scary [and] disruptive” for locals.

“As it’s telegraphed in advance, most hauliers would take fewer days of disruption where most of the work can be done completely rather than months of lane closures.”

Do lane rental schemes work?

Local authorities, meanwhile, are trying other solutions. Lane rental schemes mean utility companies are charged up to £2,500 per day for works on certain busy routes at peak times.

“A lane rental scheme that requires contractors and utility companies to pay for every day of lane closure, we believe would lead to more efficient and faster works being done,” says councillor Tom Hunt, chair of the Local Government Association’s inclusive growth committee.

At the moment only a handful of councils have these powers. MPs on the Transport Select Committee want it to be rolled out more widely across England. Ministers have said mayors will get the power to introduce these schemes in their areas.

In pictures via Getty Images

In pictures via Getty ImagesBut Bairsto of Streetworks UK argues it could end up costing customers more. “Lane rental is a cost of doing business and is passed directly on to the consumer.”

More broadly, he says, “I think we have to bear a little bit of irritation and pain from time to time, just to ensure that we have the quality and standards of utilities we need to progress as a nation.”

Ultimately, three things keep cropping up in my conversations: co-ordination, communication and duration. And while there are some proposed solutions, no clear answers are immediate.

As Bell, from National Highways, puts it: “Across all of our infrastructure, whether that’s energy, water – you could argue they have all seen a lack of investment, which is why you’re now seeing increased levels of road works as we now invest.”

And with a government that believes better infrastructure is a route to economic growth, it seems road works are here to stay.

The question is still whether they can be managed more effectively to limit the impact on daily journeys, businesses – and the collective blood pressure of the nation’s motorists.

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published – click here to find out how.

![[Aggregator] Downloaded image for imported item #514334](https://www.sme-insights.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/31761940-e590-11f0-a8dc-93c15fe68710.png.webp)