This post was originally published on this site.

Zoe KleinmanTechnology editor

BBC

BBCListen to Zoe reading this article

Back in November, I posted a note on LinkedIn about brain fog. I dashed it out in about 10 minutes – how for the first time in my 20-year career, I ended up using notes while doing live TV news thanks to the perimenopause brain fog. I didn’t expect many replies.

To my surprise, it sparked a national conversation. I was overwhelmed with wonderfully supportive messages – nearly 400 comments on LinkedIn and dozens of private messages, and hundreds more beneath a piece about it on the BBC News website. Many of them followed similar lines: calling me “brave” for speaking out. Or thanking me for “normalising” brain fog.

I didn’t feel particularly brave (or normal!) at the time – but it did spell out to me just how much shame and stigma was attached to some of the symptoms of perimenopause and menopause, even though it affects pretty much half the population at some point in their life.

Hollywood stars like Oprah Winfrey and Halle Berry have spoken out about their own experiences of menopause and its impact, as have TV presenters Davina McCall and Lorraine Kelly. Gwyneth Paltrow called for a “rebrand” of menopause back in 2018.

And there have been some changes. For example, menopause screening is to be officially incorporated into NHS health checks in England offered to women over 40 from this year. Plus, an Employment Relations Bill means that UK employers of 250 or more need to have “menopause action plans”. This comes into effect from April 2027 (and on a voluntary basis from this April).

Yet a self-selecting survey of around 1,600 women, published in October by University College London, found that more than 75% felt that they are not well-informed enough about menopause. Which suggests that something is going amiss.

What’s more, many women say there is still stigma surrounding menopause and feel they cannot openly talk about the menopause.

One woman in her 60s, an academic specialising in social policy, messaged me to say that she had started making light of her “menopausal moments” around female colleagues. But it was still “embarrassing,” she added – especially when she forgets some specific policy terms in her area of expertise.

Yet concealing symptoms, or masking menopause, can be draining.

“The energy expended in masking or making up for the challenges women face will often further deplete reserves and reduce thresholds for overwhelm,” says Fionnuala Barton, a GP and certified menopause specialist with the British Menopause Society.

This, she argues, could potentially increase the risk of burnout. And it begs the question of whether this very concealment in itself can impact lives of women too?

Menopause masking and burnout

The NHS lists 34 possible symptoms of menopause and some are more common than others. Many can feel debilitating.

One woman who contacted me after seeing my LinkedIn post explained that declining oestrogen had caused vaginal dryness, which made walking painful.

One friend revealed to me that she had developed bladder weakness. It hit her “almost overnight,” she said – now she doesn’t always make it to the toilet in time.

“It’s more annoying than anything else,” she admitted, but told me she wouldn’t want to return to an office because of it, and prefers home working.

Another woman told me she was reluctant to socialise because she felt unable to follow conversations when thick in the clouds of brain fog.

Scores of others shared their own coping strategies: some kept fans on their desks at work to manage hot flushes, others wrote notes to themselves, like I did, to get around the brain fog during meetings and presentations.

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Bloomberg via Getty ImagesOn one hand all of this speaks to the creativity and resilience of these women that they could work around what were, in some cases, such debilitating symptoms and still get on with life.

Fiona Clark, journalist and author of Menowars, says often women go on a journey when they start noticing symptoms: “In the beginning there’s confusion and denial, then there’s grief and then there’s acceptance.

“But if you’re hiding it or masking it you’re not going out and getting the help that you need.”

Menopause masking can be a particular challenge at work. There are an estimated four million women aged 45 to 55 employed in the UK, according a government report published in 2024 – this is the most common window for menopause.

Jo Brewis, professor of people and organisations at The Open University Business School, says that when people mask symptoms at work, this can lead to a set of what economists call intensive margin costs.

“In other words, the effort involved creates an extra burden for those affected.”

Some may leave their jobs altogether. An estimated one in 10 women, aged between 40 and 55, working through menopause have left a job because of their symptoms, according to a report from The Fawcett Society in 2022, which analysed data from a survey of around 4,000 UK women carried out by Savanta ComRes research consultancy.

FilmMagic via Getty Images

FilmMagic via Getty Images“This burden can take the form of making themselves less visible – such as not applying for promotions or even moving into a lower status, usually lower paid role, to be able to cope,” says Jo Brewis.

“People can also invest extra effort to avoid any perception that they are slacking off or their performance is dipping. For example, they might work longer hours to ensure they have double-checked their work if they are experiencing common symptoms like loss of focus or fatigue.”

Japanese women and the ‘second spring’

Of course, some women do have positive experiences of menopause, and it is important not to generalise experiences.

And some cultures also have different attitudes to menopause as a society. For example, the Japanese word for menopause, “konenki”, means renewal and energy.

There, it’s sometimes described as a “second spring” – which nods to a positive transition into a different phase of life.

Dr Megan Arnot, honorary research fellow in evolutionary anthropology at University College London, says: “Many countries still carry a stigma around menopause, similar to the UK, though it seems attitudes here have begun to shift in recent years.”

However, she suggests there are cultures and countries where menopause is framed more positively.

“In many indigenous communities, including Native American and Mayan cultures, menopause is seen as a transition into wisdom and leadership, granting women greater respect and influence […] Similarly, among Indigenous Australian communities, postmenopausal women often become key cultural educators and spiritual guides.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMelissa Melby, a professor of anthropology at the University of Delaware, agrees that in the West, “there is this perception that menopause is going to be horrendous, it’s going to be hard to navigate, and it’s all downhill from there,”.

“Generally, we give women symptom checklists of negative symptoms. Problems. We never ask them, did anything change during this time that was positive for you?

“If you only ask questions about negative things, you’re going to have very negative perceptions.”

She spent ten years living and working in Japan, and talking to women there left her with “a sense of potential and hope for the next phase of [her] life”.

Admittedly, I don’t currently share this view – and if my husband said that to me right now, I couldn’t guarantee his safety. But perhaps there is something in the idea of, instead of fixating on the rollercoaster of symptoms, considering the bigger picture.

No ‘one size fits all’ answer

Menopause has long been big business: there are dietary supplements, symptom trackers, therapeutic headbands, and life coaches all specialising in it. My targeted social media feeds are full of adverts for midlife natural remedies.

The menopause market was estimated to be worth more than $17bn (£13bn) in 2024, and is projected to reach more than $24bn (£18bn) by 2030.

But often none of this is enough by itself.

When it comes to the workplace, Brewis stresses that employers need to be careful about how they offer support. In her view, line managers need specific training to be able to support their teams, for example, in having sensitive conversations and working out reasonable adjustments for individuals. She adds that clearly identifying menopause as a legitimate reason for absence is also important.

“Some people will never want to disclose their menopausal status at work, no matter how compassionate or supportive their organisation is, and that is absolutely their prerogative,” she adds. “But effective menopause initiatives can and should make disclosure easier and reduce this stigma.”

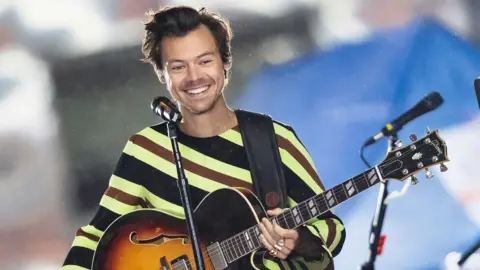

Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesUltimately, I’ve found that attitude plays a crucial role.

It was Margaret Mead, a pioneering anthropologist from the US, who coined the term “post-menopausal zest”, more than 70 years ago.

Back in the 1950s, she said: “There is no greater power in the world than the zest of a postmenopausal woman.”

So for now, that positive thinking is what many of us must cling to.

As for me, I’m going to hold onto that for as long as this lasts, and channel “konenki” as well – and take HRT.

But the outpouring of support and conversations sparked by my brain fog moment has shown me another, even more comforting fact too: that I am definitely not alone.

Additional reporting: Harriet Whitehead

Top image credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published – click here to find out how.

![[Aggregator] Downloaded image for imported item #634550](https://www.sme-insights.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/413a4630-e7cf-11f0-a8dc-93c15fe68710.jpg.webp)