This post was originally published on this site.

Raffi Bergand

David Gritten

At least 2,400 protesters are reported to have been killed in Iran during more than two weeks of nationwide unrest which has threatened the rule of the Islamic regime. Thousands more are said to have been arrested.

US President Donald Trump has repeatedly threatened military intervention if security forces kill peaceful protesters. He has also now vowed to take “very strong action” if any of the detained protesters are executed.

When did the protests begin and why are people angry?

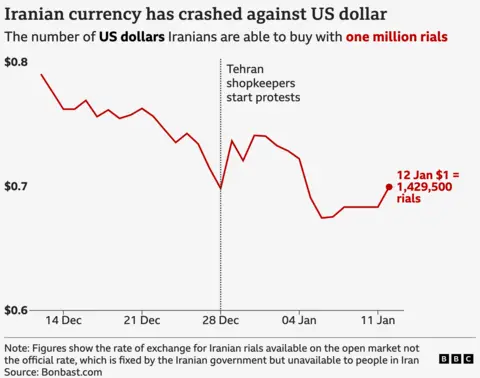

On 28 December, shopkeepers took to the streets of Tehran to express their anger at another sharp fall in the value of the Iranian currency, the rial, against the US dollar on the open market.

The rial has sunk to a record low over the past year and inflation has soared to 40%, which has resulted in crippling price rises for everyday items like cooking oil and meat. Sanctions over Iran’s nuclear programme have squeezed an economy also weakened by government mismanagement and corruption.

University students soon joined the protests and the demonstrations began spreading to other cities. There were wider calls for political change, with crowds frequently heard chanting slogans against the country’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Expressions of support for Reza Pahlavi, the exiled son of Iran’s late former shah (king), became more widespread throughout the first week of January, when thousands of people took to the streets of Tehran and other major cities.

According to the US-based Iranian Human Rights Activists News Agency (HRANA), protests have been confirmed in 187 cities and towns in all 31 of Iran’s provinces since the start of the unrest.

HRANA has not provided an estimate for the total number of people believed to have taken part, although it has said that more than 18,000 protesters have been arrested.

How are the authorities responding to the protests?

Authorities have cracked down violently. A range of weapons including water cannon, rubber bullets and live ammunition have been reportedly used against protesters. Medics said hospitals were “overwhelmed” with dead and injured.

Iran’s judiciary chief vowed “swift and harsh” punishment, warning courts to show no leniency towards “rioters”.

On 14 January, HRANA reported that 2,403 protesters, 147 people affiliated with the security forces and government, and nine uninvolved civilians had been confirmed killed since the protests began. In addition, HRANA said it had received 779 other reports of deaths that remained under review.

An Iranian official had told Reuters news agency on 13 January that 2,000 people had been killed but that “terrorists” were to blame for protesters’ deaths.

Among those reportedly killed are Amir Mohammad Koohkan, 26, who was a football coach, and Rubina Aminian, 23, a Kurdish fashion student.

On 11 January, videos emerged from the Kahrizak Forensic Centre in Tehran showing people searching for the bodies of their loved ones. The BBC counted at least 180 shrouded bodies and body bags in the footage. Around 50 bodies were visible in another video from the facility shared on 12 January.

Iran is shrouded in an internet blackout, which experts say began on 8 January. Some Iranians are managing to use Elon Musk’s Starlink satellite internet service to counter the shutdown, but the terminals are banned in Iran and authorities are reportedly attempting to trace them.

Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi said authorities had decided to cut the internet when what he called “trained terrorist groups” run from abroad became involved in the protests.

On 14 January, Araghchi’s ministry cited him as telling his counterpart from the United Arab Emirates that “calm has prevailed [in Iran] thanks to the vigilance of the people and law enforcement forces”.

His comments echoed those of the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who had told supporters at state-organised rallies across the country on 12 January that they had “neutralised the plans by foreign enemies that were meant to be performed by domestic mercenaries”.

Who is in charge of Iran?

Office of the Iranian Supreme Leader/WANA (West Asia News Agency)

Office of the Iranian Supreme Leader/WANA (West Asia News Agency)Iran – a major power in the Middle East with a population of around 90 million – is ruled by the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

It has a parliament but this is heavily influenced by MPs loyal to Khamenei, who has the final say on the most important matters – including how to deal with the protests.

Iran was a key Western ally until 1979, when the shah was overthrown in an Islamic revolution and a devout Shia Muslim regime took over.

Since then the country has been run along strict religious lines. Criticism of the regime is not tolerated and personal freedoms have been heavily restricted.

A law requiring women to wear headscarves has been a particular source of deep resentment – and fuelled mass protests in 2022.

Iran has one of the highest execution rates in the world and is consistently ranked among the worst human rights offenders.

Western countries have had strained relations with Iran since the revolution, with the US and Iran becoming major adversaries.

Washington accuses Iran of destabilising the Middle East, especially through its support of armed groups, including Hamas in Gaza, Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen.

For its part Iran accuses the US of interfering in the region.

The US has been a leading opponent of Iran’s nuclear programme, claiming it aims to build a bomb – something Iran denies. It bombed Iran’s nuclear sites in June 2025, while international sanctions on Iran over its nuclear activities have had a drastic effect on Iran’s economy.

What has Donald Trump said about US military action?

Donald Trump and his administration have repeatedly threatened to intervene in Iran if authorities killed peaceful protesters.

On 2 January, after the deaths of several people were reported, he said in a post on Truth Social that the US would come to the protesters’ rescue. “We are locked and loaded and ready to go,” he wrote.

On 11 January, Trump announced that countries doing business with Iran faced a 25% tariff on their trade with the US, ramping up pressure on Tehran.

A US official also told the BBC’s US news partner CBS that Trump had been briefed on options for military strikes on Iran.

The Wall Street Journal reported that other options available included imposing further sanctions, boosting anti-government voices online, or using cyber-weapons against Iran’s military.

On 13 January, the president called on Iranians to keep protesting, telling them in another Truth Social post to “take over your institutions” and “save the names of the killers”. “They will pay a big price,” he warned. He also said that “help is on its way,” without giving any details.

Later, he told CBC that the US would take “very strong action” against Iran if authorities executed protesters. “If they hang them, you’re going to see some things,” he said.

His comments came as he convened his national security team, amid mounting speculation about what action the US could take.

Trump had said on 11 January that Iranian leaders “want to negotiate” because “they are tired of being beat up by the United States”.

On 12 January Iran’s Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi warned that the country was “fully prepared for war” if attacked, but added that it was also ready for negotiations that were “fair”.

Why is it difficult to get information about what is happening in Iran?

Iran restricts international news organisations like the BBC from operating inside the country. The state broadcaster and official agencies follow strict guidelines dictated by the state. Independent Iranian journalists routinely face persecution and harassment for any reporting that is critical of the authorities.

Internet access is also heavily restricted, with most of the major social media platforms and Western news agencies banned. However, Iranians have become adept at using a variety of methods such as VPNs to circumvent these restrictions.

But the ongoing blackout has almost completely cut off Iranians from the outside world, although international phone calls reportedly began to work again on 13 January.

Before the blackout came into force on 8 January, hundreds of videos from the protests were posted on social media. Iranians regularly spoke to foreign-based journalists to provide eyewitness accounts of the protests.

Since then, the flow of videos has been significantly reduced, and it has become extremely difficult to speak to people inside.

A minority of Iranians have access to Starlink, and have been posting a few videos of the latest developments.

Some have also managed to momentarily connect to the internet and share their observations with journalists, friends and family members living abroad.

Additional reporting by Tom McArthur and Shayan Sardarizadeh.

![[Aggregator] Downloaded image for imported item #550442](https://www.sme-insights.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/3676f4c0-f079-11f0-a422-4ba8a094a8fa.png.webp)